I was scrolling through my Instagram, which is 90% cat videos, gardening, and travel sites — all of which make me very happy — and I came across one of the many accounts about Italy that I follow.

The post was about how Firenze celebrates the feast day of San Giovanni Battista, aka St. John the Baptist, patron saint of Firenze, today, June 24th.

Many acts of celebration take place in the days leading up to the festa, and an entire day of festivities takes place on the actual saint’s day. You can read about some of them here:

Visit Tuscany

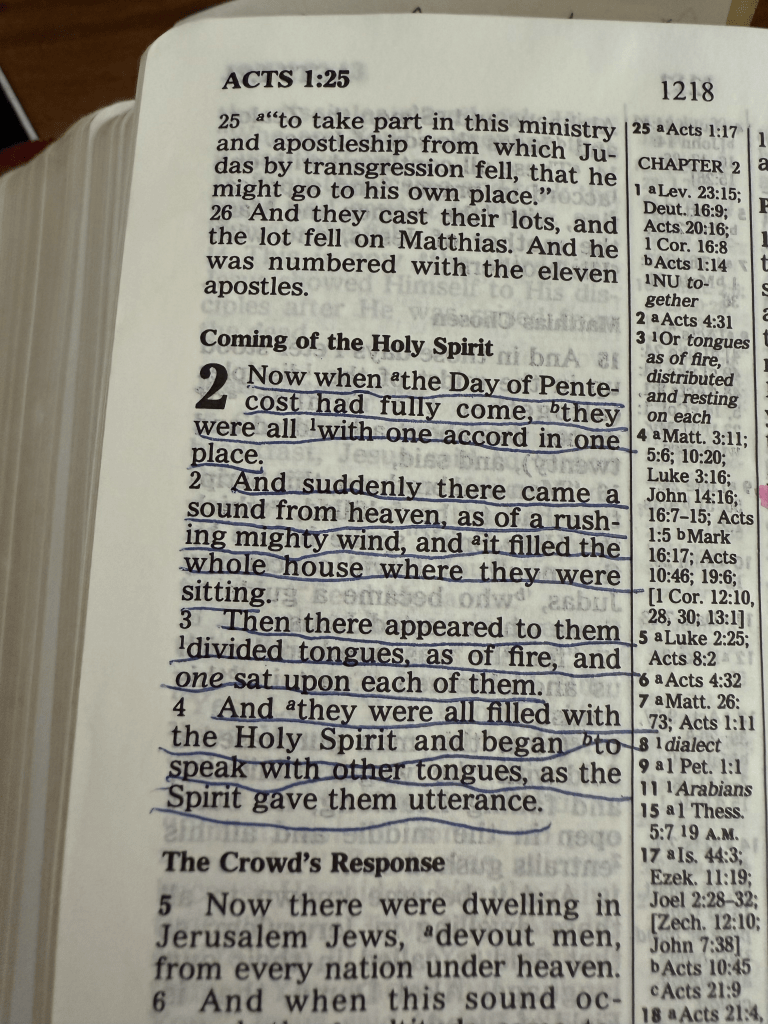

Not being Catholic, I have never given much thought to feast days or patron saints until I started teaching and spending time in Italy. Growing up as a Pentecostal/Evangelical Christian, anything decorative bordered on idolatry. Pentecostal, briefly, is part of the Evangelical movement based on the day of Pentecost. Pentecost is believed to be the day that the Holy Spirit descends on the disciples. The event is found in Acts chapter 2.

“And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.”

Acts 2:4

This is the religion of my family. Speaking in tongues. Dancing in the spirit. Tent revivals in the sweltering summer heat of Kentucky. Church people being consumed by the spirit and passing out. Though I am not sure if the passing out was from the spirit or from the oppressive heat of tent revivals (my Grammaw always had a church fan in her purse), or the random appearance of a snake in the hands of someone demonstrating the power of the Lord to suppress Satan (my Grammaw did not have a snake in her purse).

The Pentecostal churches I know were devoid of decoration and very simple because, like Puritans and Congregationalists, people felt that decoration and ritual distracted from their personal relationship with God. And there were never images of anyone in our churches. No Mary, No saints. No Christ child, or Jesus at all, really. We had images of Jesus, on the cross or as a young man, but those weren’t hung in church.

And we certainly didn’t have a home altar. It’s impossible not to appreciate the many murals and altars erected in nearly every (probably every) neighborhood in every city in Italy.

Some of these altars or murals are simple. Some are very grand. Many are of the Madonna and Child, but many are of saints.

Even on the side of the Funiculare hill up to Montecatini Alto there was a small altar to the Madonna and Child. I missed taking a picture of it and would have missed it altogether if we hadn’t noticed the lovely Italian woman standing in front of us on the car balcony hadn’t thrown a kiss to the Madonna as we passed.

And, as we learned in Napoli, you could say that the altars and murals reflect a slightly modern take on a holy trinity—Madonna, Maradona, and Sophia.

As I read about the upcoming celebration of San Giovanni Battista, I was also reminded of the patron saint of Napoli, Saint Januarius, better known as San Gennaro. Saint Januarius is the Roman/English name, and San Gennaro is the same name in Italian.

I have visited many churches and basilicas throughout Italy, and many of them display relics, with heads, fingers, and blood being among the most treasured. The same is true of the cathedral in Napoli. However, this one is uniquely different because the Chapel of San Gennaro, where the relics are kept, is the only chapel inside a cathedral in Italy that does NOT belong to the Vatican.

If you want to read more about the amazing history of San Gennaro: https://www.holyart.com/blog/saints-and-blessed/the-story-of-san-gennaro-the-patron-saint-of-naples/

Maybe that’s why I was fascinated with San Gennaro, or maybe it was the story of his blood liquefying three times a year—on September 19 (his feast day), on December 16 (which marks the day that San Gennaro is believed to have saved Napoli from the eruptions of Mount Vesuvius) and on the first Sunday in May. This day in May honors the day San Gennaro’s relics were transferred to the chapel.

As part of the ritual of liquefication, the vials, or ampoules, of blood are brought out and placed in a reliquary for the Bishop of Napoli to present to the crowd. Hundreds of people pack the chapel, the cathedral, and the streets of Napoli to witness the miracle. After prayers led by the Bishop of Napoli and repeated by the devote people, the blood liquefies. The people of Napoli take the liquefaction as a sign of good fortune and prosperity to come. When the blood does not liquefy, the event foreshadows a precarious and ominous future.

There are several times the blood did not liquefy and plagues, wars, and earthquakes followed. Most recently, the blood failed to liquefy on December 19, 2020—believed by many to be a sign of the continuation of COVID and the financial crisis that resulted.

Read more: Blood of Naples saint fails to liquefy in what some see as a bad omen. https://www.reuters.com/article/lifestyle/blood-of-naples-saint-fails-to-liquefy-in-what-some-see-as-bad-omen-idUSKBN28Q2UX/#:~:text=Scientists%20say%20the%20substance%20inside,killing%20more%20than%203%2C000%20people.

The reliquary stays on display for eight days. People are invited to touch and to kiss the sacred vessel holding the blood of their beloved saint. I love the entire ritual. I love the glamor of the Chapel of San Gennaro. I love the treasures and relics. I love the history. I love the devotion. And, I love the faith and belief of the people.

I claim no religion or denomination now, but I had plenty of it growing up. Now, as I learn to appreciate cultures and religions from all over the world, I am reminded of things that have stuck with me from childhood. Although I have separated myself from religion, there are a few guiding principles that I have learned, which I feel speak more to humanity than to religion. The faith of those devoted to San Gennaro brings back memories of many sermons, and also feels very relevant to all of us today. And seeing the news of San Giovanni’s feast day, I was thinking about how these feast days give people hope. Something I need more of lately.

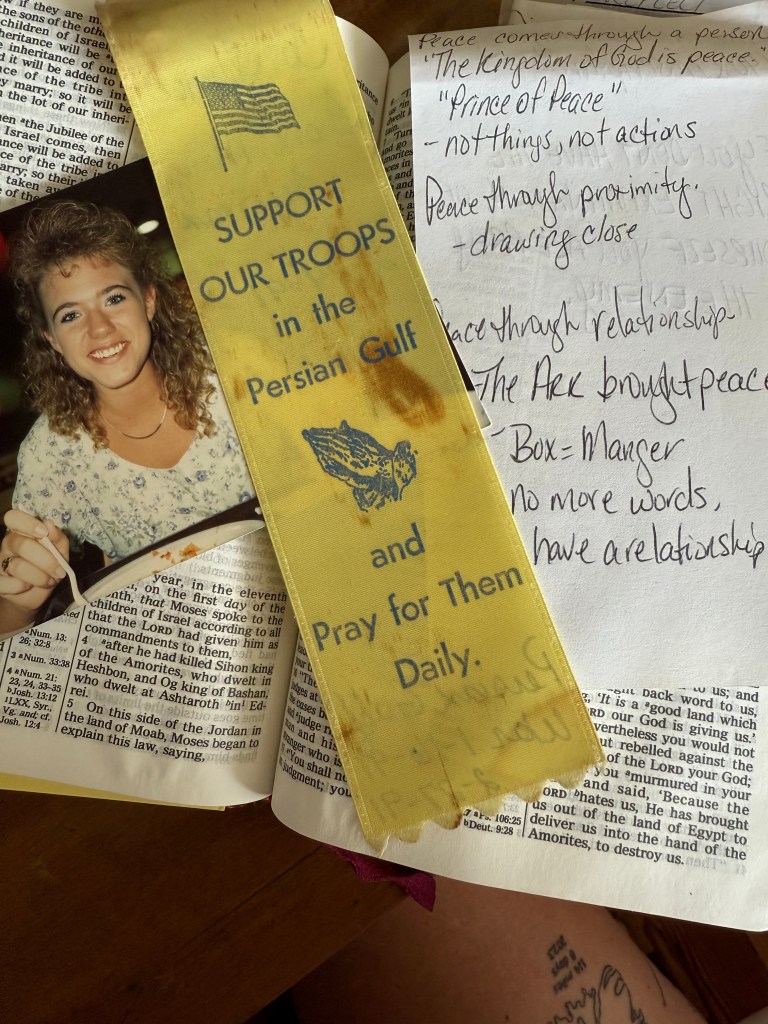

I got out my Bible. It’s not kept in any reverent place in the house like the Puritans. It’s just on a shelf of what I call keeper books. In fact, it was squashed between two novels by Louisa May Alcott.

I dug it out because I was reminded of a scripture my Papaw used so often in sermons.

“Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”

I confess I had to Google it first because I only remembered it was in the New Testament, but I had no recollection of which book or verse. Turns out, it’s Hebrews 11:1.

I also struggled to remember my Papaw’s voice and his explanations for the relevance of this scripture. I still don’t remember. And after trying to force myself into the words and explanations of this in the past, I let it go. Because, like my religion and denomination, I’ve let that go too. I look at these scriptures with new eyes now. It’s important for me to use the knowledge and understanding I have gained since those early memories. Though my Bible is filled with notes in the margins, memories on scraps of paper from many years, earmarks for places I have no recollection of making, and strange tidbits….

…it is like any other book to me in that it provides a starting point for making sense of things in my own world.

I used the reference to other scripture listed in the center concordance that sent me to Romans 8:24.

While I was searching for the other scripture, this was the one I was meant to see: Romans 8:24-25.

“For we were saved in this hope, but hope that is seen is not hope; for why does one still hope for what he sees? (8:24) But if we hope for what we do not see, then we eagerly wait for it with perseverance. (8:25)”

My Scorpio tail went up almost immediately. It happens when I feel the need to defend myself or someone or something else, and it also happens when I feel challenged, as if I need to prove myself or prove something to myself. My response also made me smile, because this is the exact feeling I would get sitting in graduate school when some theory, concept, or argument challenged me. And those are the moments I knew would lead to research and revelation.

As I read and re-read these passages, and those before and after, I was irritated by the ideas here.

“but hope that is seen is not hope, for why does one still hope for what he sees?”

But, this is suggesting a sort of blind hope! I have to keep in my mind that this book, like all others, is arguing from a specific place. And here, in the Bible, this is about trusting in the Holy Spirit—which we cannot see. The hope, this unseen hope, equals belief in the Holy Spirit. And that is fine. I can still appreciate this concept. But….

… the rituals on feast days of saints are a sort of seen hope. Maybe because I’ve fallen for all things Italian, but more because I’ve learned to understand things in my own way, these processions, relics, and rituals bring hope to people. I still try to work out the divide between the religion of my childhood—the plain, unadorned, simplistic church—and the chapels and cathedrals and basilicas of other religions with their precious stones and metals, and their glamorous altars.

These beautiful places of worship and these rituals inspire both devotion and faith. These are things that can BE seen and are part of what I believe gives them hope. I don’t know much about their religiosity, and I am likely missing a real and fervent explanation for the connection. But, I am making sense of it in my own way.

Having studied the Puritans and the formation of the Congregational Church for many years, their goal was to remove the adornments and reliquaries that these men believed led people away from God, because they reflected the corruption of the Catholic Church in selling salvation or favor with God. And I get that. After all, some of the most beautiful chapels in Italy were funded by wealthy families hoping to win forgiveness from God.

Consider the beautiful Arena Chapel, in Padova, Italy. It is also known as Scrovegni Chapel because it was paid for by Enrico Scrovegni.

Photo credit: https://www.italia.it/en/veneto/padova/things-to-do/scrovegni-chapel-in-padua

Enrico Scrovegni came from a long line of moneylenders, not the most noble of professions during the Medieval period. His father was depicted in Dante’s Divine Comedy as one of those cast into hell to burn for the sin of ‘usury.’ As a means to save himself from a similar fate, Enrico hired Giotto di Bondone to paint the frescoes of the chapel (and possibly design the chapel itself).

No doubt there was an attempt to buy salvation here. But I won’t judge anyone else’s motives, not even Enrico Scrovegni. I like to think that people who pay for a chapel or even those who celebrate feast days have a pure heart. I like to think that the devout people of Napoli, who crowd the chapel, the cathedral, and the streets, are a hopeful people. I imagine them waiting to kiss the reliquary of liquefied saint’s blood, perched on the pews and rubbing their rosaries and praying. I imagine that they see what I see…shining gold, glittering jewels, blindingly bright marble, the sparkling Bishop’s mitre, and the gleaming crozier. And, they, like me, are hoping.

I believe you can draw hope from the unseen and from the seen. I need to believe that because “faith is the substance of things hoped for,” and hope seems to be in short supply these days. Hope seems to be dwindling.

And what happens when the hope is gone? What faith is left if there is no substance?

I’ll take hope from wherever I can find it—seen or unseen. And I like that rituals and iconography and relics provide hope. I don’t know if my boys, who also profess to be of no religion, have ever been in a Catholic Church before. But as they walked out of Chiesa di San Michele in Foro and the Duomo di San Martino in Lucca, they remarked on how they could now understand why some people went to church. They were moved by the visible devotion of murals and altars and the sight of people praying their rosaries, even among the gawking tourists.

After all this thinking and writing, I know I won’t remember which book or verse these scriptures are in. What I will continue to think about are memories of how my Papaw, who I thought was so religious and so devout, struggled with understanding and accepting his own faith in himself, in God, and, I think, his faith in others.

I like to think that the faith within my boys was fueled by what they saw and what they felt in those places. What they saw was hope. It wasn’t unseen. And I hope they carry that with them and that it continues to fuel their faith. Religious or not, I have faith, and I think they do as well, in a world where we can accept and love the things and the people we encounter, whether we understand them or not.

And I hope that the feast day of San Giovanni brings a similar hope to the people of Firenze today. Buona festa, Firenze! Grazie a Dio!